Founding Chamber

The founding chamber is a solitary cavity excavated by the newly mated Atta queen during the claustral phase of colony founding [1]. It is typically located ~10–30 cm beneath the soil surface and is connected to the outside by a short tunnel that the queen immediately seals after excavation [1]. This chamber houses the queen and later her brood and initial fungus garden. These conditions were recreated in the founding chamber of the fromicarium.

Sources: [1] Andrade Sousa, Kátia & Camargo, Roberto da & Caldato, Nadia & Farias, Adriano & Calca, Marcus & Dal Pai, Alexandre & Matos, Carlos & Zanuncio, José & Santos, Isabel & Forti, Luiz. (2022). The ideal habitat for leaf-cutting ant queens to build their nests. Scientific Reports. 12. 10.1038/s41598-022-08918-2.

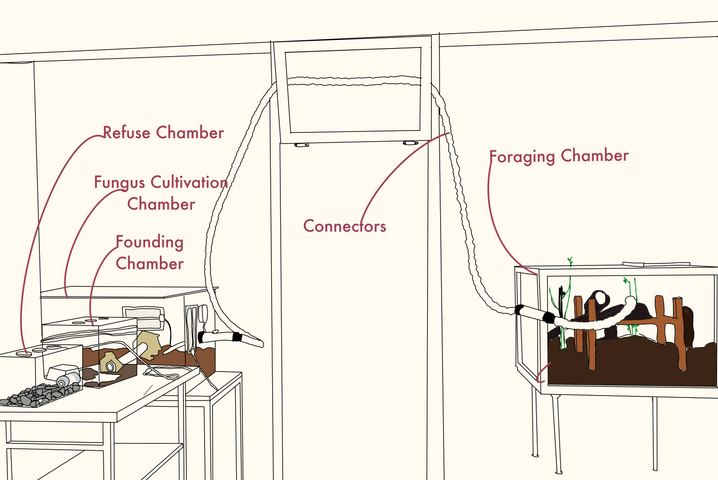

Fig. 2. Founding Chamber. Houses the queen and initial fungus garden.

Fig. 3. Fungus Cultivation Chamber. The chamber where the fungus garden is housed.

Fungus Cultivation Chamber

Mature Atta sexdens nests contain numerous large fungus-garden chambers. In A. sexdens, these chambers are semi-ellipsoidal in shape and typically arranged in clusters beneath the prominent mounds of excavated soil on the nest surface [2]. The fungus chambers are distributed laterally at moderate depth in the nest profile, often connected by tunnels to adjacent chambers and to the surface [2].Worker ants transport fresh foliage into this chamber, where “gardening” workers chew the plant material into a pulp, inoculate it with fungal mycelium, and add saliva and anal gland secretions to promote fungal growth [3].

The chamber thus houses the fungus garden along with eggs, larvae and even the queen, forming the metabolic and reproductive heart of the colony [3]. Workers tend these gardens continuously, removing any mold or parasites and redistributing healthy garden fragments among chambers as needed.Fungus cultivation chambers are maintained at very high humidity and stable temperatures. Atta workers actively concentrate the fungus in chambers at near-saturated humidity: experimental colonies relocate gardens to ~98% relative humidity when given a choice [4]. In natural nests, measurements show that the fungus-garden areas of A. sexdens maintain RH above 90% throughout the year [4]. This humid, warm microclimate prevents the delicate fungal crop from desiccating. Ventilation and chamber placement are arranged so that temperature and CO₂ remain in a range optimal for fungal growth [5].

Sources: [2] Forti, L.C.; Protti de Andrade, A.P.; Camargo, R.D.S.; Caldato, N.; Moreira, A.A. Discovering the Giant Nest Architecture of Grass-Cutting Ants, Atta capiguara(Hymenoptera, Formicidae). Insects 2017, 8, 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects8020039 [3] Weber NA. Fungus-growing ants. Science. 1966 Aug 5;153(3736):587-604. doi: 10.1126/science.153.3736.587. PMID: 17757227. [4] Roces, F., Kleineidam, C. Humidity preference for fungus culturing by workers of the leaf-cutting ant Atta sexdens rubropilosa. Insectes soc. 47, 348–350 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1007/PL00001728 [5] Römer, Daniela & Bollazzi, Martin & Roces, Flavio. (2019). Leaf-cutting ants use relative humidity and temperature but not CO2 levels as cues for the selection of an underground dumpsite. Ecological Entomology. 44. 10.1111/een.12727.

Foraging Chamber

This chamber is used only to introduce fresh food (leaves). By confining foraging to one box, unused leaf fragments and excess food can be cleaned without disturbing the fungus [6].

Sources: [6] Nogueira BR, de Oliveira AA, da Silva JP, Bueno OC. Collection and Long-Term Maintenance of Leaf-Cutting Ants (Atta) in Laboratory Conditions. J Vis Exp. 2022 Aug 30;(186). doi: 10.3791/64154. PMID: 36121257.

Fig. 4. Foraging Chamber. Where the food is placed.

Fig. 5. Refuse Chamber. Where the dead ants are placed, to keep contaminants away from the fungus.

Refuse (Death/Midden) Chamber

Leaf-cutting ants regularly trim older fungus and throw away refuse (dead ants). Providing a dedicated waste chamber keeps contaminants away from the fungus. In their natural habitat Refuse or midden chambers are buried deep in the nest, usually beneath the main soil mound and below the level of most garden chambers [7]. Atta sexdens colonies may have dozens or hundreds of these waste cells: one detailed excavation found 296 underground refuse chambers containing ~475 kg of trash [7]. Waste chambers are often conical or funnel-shaped with rough, irregular walls [2]. They are commonly located at greater depth than the fungus chambers, reflecting their role in waste sequestration [5].

Sources: [7] Bot, A. & Currie, C. & Hart, Adam & Boomsma, Jacobus. (2001). Waste management in leaf-cutting ants. Ethology Ecology & Evolution - ETHOL ECOL EVOL. 13. 225-237. 10.1080/08927014.2001.9522772.

Connectors

Chambers are connected using hose connectors or PVC tubes with an ideal diameter of 5 cm. With the right accessories, longer distances can be created, allowing you to closely observe the ants at work and watch them transport their leaves [8].

Sources: [8] https://www.myants.de/atta-sexdens-oxid/?srsltid=AfmBOoox_FXFbY8ief5QwFCFTLx_CVBgcsohEWpOQkmxAP0SSXdfmv8I last used on 05.06.2025

Fig. 6. Connectors. For the ants to walk from one chamber to the other.

Fig.7a. Temperature and Humidity Control.

Fig. 7b. Humidifier.

Measuring the Temperature and Humidity

In the formicarium, the colony was maintained under carefully controlled temperature and humidity conditions to support stable fungal cultivation and colony development. The fungus cultivation chamber was kept at a constant temperature of 25–27 °C, replicating the thermal environment typically found in mature underground nests [9].Heating was provided via an external heat mat and measured with this thermometer, that also shows the humidity.

The humidity within the fungus cultivation chamber was maintained at 90–95%, consistent with the high-moisture conditions required by the fungus [9]. This was achieved through spraying water inside the tank form time to time and at the end we started to use a humidifier.

[9] Sousa KKA, Camargo RS, Caldato N, Farias AP, Calca MVC, Dal Pai A, Matos CAO, Zanuncio JC, Santos ICL, Forti LC. The ideal habitat for leaf-cutting ant queens to build their nests. Sci Rep. 2022 Mar 22;12(1):4830. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-08918-2. PMID: 35318404; PMCID: PMC8941024.

The Process

The construction of the formicarium began with the formation of a specialised team dedicated solely to designing and building the ant habitat. This group took the lead in transforming ideas into a functioning habitat in which the ants could live, grow, and be studied.

Our first task was to review the materials left behind by the previous class. We sorted through them to identify what could still be used and what needed replacing.

Next, we planned a beta version, which is a temporary prototype that would enable us to test our setup before committing to the final version. We opted for a small main chamber connected to a food chamber.

Once the plan had been finalised, we thoroughly cleaned the containers that would house the ants, ensuring a safe environment. We then filled them with suitable material and set up a heating system to simulate tropical conditions. Soon after, the ants arrived, and we observed how they interacted with the environment we had created for them.

The first few weeks with the colony helped us identify areas for improvement. For instance, we realised the importance of maintaining stable temperature and humidity levels in the main chamber. We used these insights to design the final version, ensuring it would provide more space, digging opportunities and a more stable climate.

After cleaning and filling the new main chamber, we connected it to the old one in the hope that the colony would move in. After the ants had accepted their new home and moved the fungus there, we connected a new, larger food chamber to it via a tube. They explored it soon after. We converted the old food chamber into a death chamber, which is a designated area for dead ants to prevent contamination of the living space.

One of the biggest issues with the final version was ensuring stable temperature and humidity levels, which are crucial for the health of the colony and their fungus. We also had to decide whether to cover the entire chamber with a lid, which would help to conserve moisture but could reduce airflow. Ultimately, we opted for two plexiglass plates, and this indeed increased the humidity. Furthermore, we suddenly discovered unwanted fruiting bodies of a foreign fungus growing in the main chamber, likely due to hyphae in the substrate that we had used. Fortunately, they weren’t toxic or harmful to the ants. The fruiting bodies died after a few weeks, but we never found out what species of fungus they were.

Despite the challenges involved, building the formicarium was a valuable learning experience. It required us to demonstrate problem-solving, teamwork, and adaptability, which are all essential skills in scientific work. Ultimately, we succeeded in creating a stable habitat that supports the ant colony and provides a foundation for further research and observation.

References

[1] Andrade Sousa, Kátia & Camargo, Roberto da & Caldato, Nadia & Farias, Adriano & Calca, Marcus & Dal Pai, Alexandre & Matos, Carlos & Zanuncio, José & Santos, Isabel & Forti, Luiz. (2022). The ideal habitat for leaf-cutting ant queens to build their nests. Scientific Reports. 12. 10.1038/s41598-022-08918-2.

[2] Forti, L.C.; Protti de Andrade, A.P.; Camargo, R.D.S.; Caldato, N.; Moreira, A.A. Discovering the Giant Nest Architecture of Grass-Cutting Ants, Atta capiguara(Hymenoptera, Formicidae). Insects 2017, 8, 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects8020039

[3] Weber NA. Fungus-growing ants. Science. 1966 Aug 5;153(3736):587-604. doi: 10.1126/science.153.3736.587. PMID: 17757227.

[4] Roces, F., Kleineidam, C. Humidity preference for fungus culturing by workers of the leaf-cutting ant Atta sexdens rubropilosa. Insectes soc. 47, 348–350 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1007/PL00001728

[5] Römer, Daniela & Bollazzi, Martin & Roces, Flavio. (2019). Leaf-cutting ants use relative humidity and temperature but not CO2 levels as cues for the selection of an underground dumpsite. Ecological Entomology. 44. 10.1111/een.12727.

[6] Nogueira BR, de Oliveira AA, da Silva JP, Bueno OC. Collection and Long-Term Maintenance of Leaf-Cutting Ants (Atta) in Laboratory Conditions. J Vis Exp. 2022 Aug 30;(186). doi: 10.3791/64154. PMID: 36121257.

[7] Bot, A. & Currie, C. & Hart, Adam & Boomsma, Jacobus. (2001). Waste management in leaf-cutting ants. Ethology Ecology & Evolution - ETHOL ECOL EVOL. 13. 225-237. 10.1080/08927014.2001.9522772.

[8] https://www.myants.de/atta-sexdens-oxid/?srsltid=AfmBOoox_FXFbY8ief5QwFCFTLx_CVBgcsohEWpOQkmxAP0SSXdfmv8I last used on 05.06.2025

[9] Sousa KKA, Camargo RS, Caldato N, Farias AP, Calca MVC, Dal Pai A, Matos CAO, Zanuncio JC, Santos ICL, Forti LC. The ideal habitat for leaf-cutting ant queens to build their nests. Sci Rep. 2022 Mar 22;12(1):4830. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-08918-2. PMID: 35318404; PMCID: PMC8941024.